Understanding Distillers Malt, Part 1

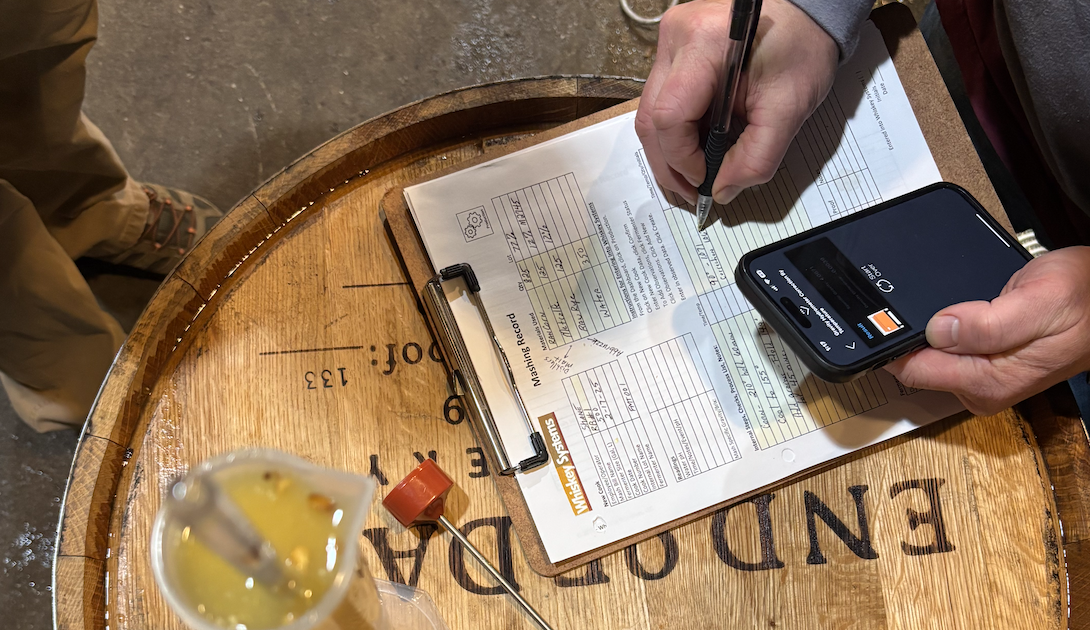

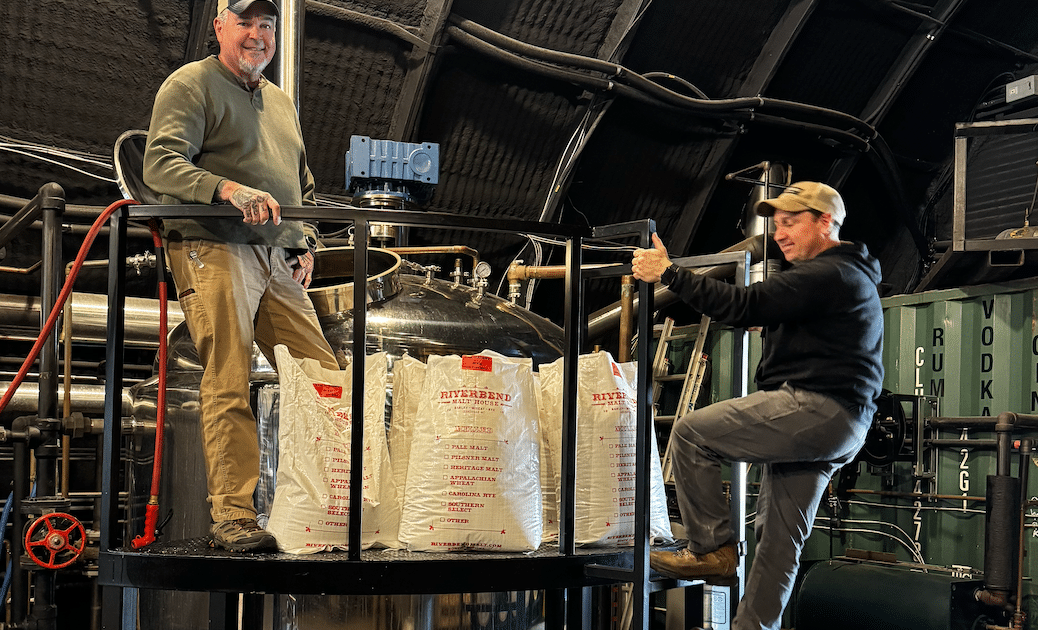

Photos courtesy EOD Distillery

Since the inception of Riverbend Malt House, we have been learning how to work with what grows in the South to produce not just high-quality beers, but also spirits. This exploration has plunged us into the often polarizing conversation about distillers malt. What is distillers malt? What’s the optimal enzymatic content for converting starch, and how does that vary across styles of spirits?

The answers to these questions usually vary depending on who you ask.

Our deep dive started with 6-row Thoroughbred barley that was originally intended to feed cattle rather than fill mash tuns. Working with our farm partners and honing our craft helped elevate this humble ingredient into award-winning whiskey!

As the quest for a truly local Bourbon recipe intensifies, we find ourselves at yet another inflection point. Our current 2-row barley varieties offer a strong enzyme package and great flavor,but not quite what large-scale distillers require. For example, we can push diastatic power levels to the 170-180 range, distillers malt spec is >250. On the alpha amylase front, distillers usually look for >85, and we have landed in the 65-70 range.

Why the enormous appetite for enzymes in distillers malt, you ask?

Well, they often use as little as 5% malt in their recipes, which puts a tremendous amount of pressure on the enzymes to convert a large amount of starch into fermentable sugar in a short amount of time. This is compounded by the intricate production schedules that can include dozens of active fermentations and processing in column stills that require constant “feeding”.

A simple question was posed: Can we make up for the lack of enzymes by adding a bit more malt to the recipe? This would allow the finished spirit to remain very much in the realm of the legally defined Bourbon, but also allow for 100% of the ingredients to be sourced locally.

We partnered with our friends at End of Days Distillery to test the limits of our Speakeasy Distillers Malt, comparing it to the well-known Metcalfe spring barley sourced from traditional barley-growing regions of the Pacific Northwest.

At EOD, we made three batches of Bourbon. Equal amounts of Speakeasy and Metcalfe were utilized in each to determine a performance baseline. The third batch used twice as much Speakeasy and less raw corn, with the hope that spirit yield and starting gravity would surpass, or at least equal, that of the Metcalfe batch.

Recipes:

Batch #1

75% raw corn

13% raw rye

12% Metcalfe distillers malt

Batch #2

75% raw corn

13% raw rye

12% Riverbend Speakeasy

Batch #3

63% raw corn

13% raw rye

24% Riverbend Speakeasy

The Results

Batch #1 had a OG of 1.071

Batch #2 had a OG of 1.076

Batch #3 had a OG of 1.073

The results were inconclusive, but were not supportive of the “more Speakeasy” approach. After talking with Harmonie Bettenhausen of the James B Beam Institute and Campbell Morrissy from pFriem Family Brewers, we learned that enzymes don’t scale linearly— especially in a high-adjunct environment. When you’re working with raw grains like corn and rye that don’t contribute enzymes, you’re depending entirely on your malt to do several things –

Break down protein matrices around starch granules (proteolytic activity), break down structural carbohydrates like β-glucans (viscosity control), and convert liberated starch into fermentable sugars (amylase action). If a malt isn’t strong enough enzymatically, adding more of it can actually flood the mash with starch that never gets fully broken down— so you’re adding extract potential, but not the keys needed to unlock it. That’s what we likely saw in Batch 3: more Speakeasy distillers malt = more starch available, but not more sugar in solution.

While not exactly the news we wanted, these experts proposed another route to achieve better conversion” a “pre malt” addition in which 10 to 20% of the total malt utilized is strategically placed to do some early enzymatic heavy lifting before the cook. Using the pre-malt at a low-temp rest helps to unlock the starches in the corn and rye when they’re added later, especially when no exogenous enzymes are used. By adding the pre-malt at around 125–135°F before adding corn to the cook (and raising the temp), they’re setting up to get better gelatinization and make the most of the malt’s enzyme package later in the mash/cook.

We’ll share results from our next round of trials in Part 2. Stay tuned for more information!

Got a question about Riverbend Speakeasy distillers malt? Give us a shout.